CASE STUDIES

NDVI isn’t the destination. It’s the coarse map that tells you where true leaf‑level diagnostics should begin.

Co‑Pilot (ChatGPT5.1) is a great adviser. I asked Copi (that’s how I call it):

What is the goal of agricultural remote sensing?

The beautifully phrased reply was:

“At its core, the goal of agricultural remote sensing is to give farmers and agronomists accurate, timely, and actionable information about their fields, without needing to physically inspect every part of them.”

Let’s break this down. The goal is to provide information that is:

- Accurate

- Timely

- Actionable

without sending scouts to the field or samples to a lab.

Will satellite or high‑altitude drone imagery ever deliver that?

Short answer: They will contribute, but they will never fully replace low‑altitude, high‑resolution sensing.

And the latest research reinforces this.

1. Satellites: Great coverage, limited availability and precision

Satellites offer:

- Large‑scale, continuous monitoring

- Frequent revisits

- Broad spectral coverage

But they face hard physical limits:

- Cloud contamination drastically reduces usable data

- Spatial resolution is too coarse for plant‑ or even canopy‑level diagnostics

- Signal mixing (soil + canopy + shadows) reduces accuracy

- Temporal gaps mean fast‑developing stresses are missed

Even with machine learning, satellite‑only biomass estimation is far less accurate than drone‑based measurements.

2. High‑altitude drones: Better than satellites, but still not enough

High‑altitude UAS (around 100 m) improve:

- Flexibility

- Revisit rate

- Some resolution

But they still suffer from:

- Atmospheric distortion

- Lower spatial resolution than low‑altitude flights

- Reduced signal‑to‑noise ratio

- Difficulty capturing fine‑scale stress indicators (early disease, nutrient gradients, etc.)

Research consistently shows that high‑resolution UAS data dramatically outperforms satellite data for biomass, stress detection, and canopy characterization.

3. What the research points to: Fusion, not replacement

The most advanced studies conclude that the future is integration, not substitution:

- Combining UAS and satellite imagery improves accuracy and timeliness

- Fusion techniques (pixel‑based, feature‑based, decision‑based) enhance crop monitoring

- Satellites provide context; drones provide precision

But neither can replace low‑altitude, high‑resolution multispectral imaging when the goal is:

- Early disease detection

- Nutrient stress mapping

- Flower/fruit identification

- Plant‑level phenotyping

- Accurate biomass estimation

These require leaf‑level, high‑resolution, high‑quality spectral data, something only low‑altitude platforms can deliver.

Bottom line

Satellites and high‑altitude drones will continue to improve, but they will never deliver the plant‑level precision needed for truly actionable agronomic insights.

They will:

- Provide context

- Enable regional monitoring

- Support long‑term trends

But they will not replace:

- High‑resolution, low‑altitude multispectral imaging

- Close‑range remote sensing

- Plant‑level diagnostics

This is exactly why Agrowing exists

Agrowing was established to acquire the most valuable agricultural insights, the ones detectable at the millimetre, not metre or centimetre, scale.

Our sensors and imaging solutions enable near real‑time, leaf‑level, high‑resolution multispectral data analyses, capturing the spectral signatures of pests, diseases, nutrient deficiencies, and other vegetation phenomena.

Because in the real world:

- Leaves never lie flat like they do in the lab

- The sun is always (relatively) moving

- Low resolution blends leaves, stems, flowers, and soil into noisy pixels

Instead of guessing from high‑altitude metrics like NDVI, MSAVI, GNDVI, or ARVI, Agrowing enables using them (and many others) as an initial zonation step, and then capturing 11–15‑band, 1 mm/pixel imagery at 5–7 m altitude.

This enables accurate, trustworthy identification of vegetation issues.

Late blight doesn’t get confused with Alternaria.

Weed species can be classified precisely for the correct herbicide.

The attached video demonstrates this. The late‑blight image of the animation was captured at 3m altitude in a UK potato field.

AquaPixel identifies

Ben Machnes of AquaPixel writes: “Thrilled to see AquaPixel featured and recognized for our joint mission to make water intelligence Precise. Measurable. Real.

Huge thanks to Ira Dvir and Agrowing for the partnership, technology excellence, and trust in our vision. Together, we’re transforming remote sensing into environmental insight — empowering water authorities and decision-makers worldwide to safeguard one of our most vital resources.

Let’s make water certainty the new global standard.”

Captaim Aurelien Schlossman used Agrowing’s quad sensor with AI to detect human remains buried for three years!

https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7374068532772446210/How can LIDAR be an asset in the turf industry? This one image speaks volumes of data.

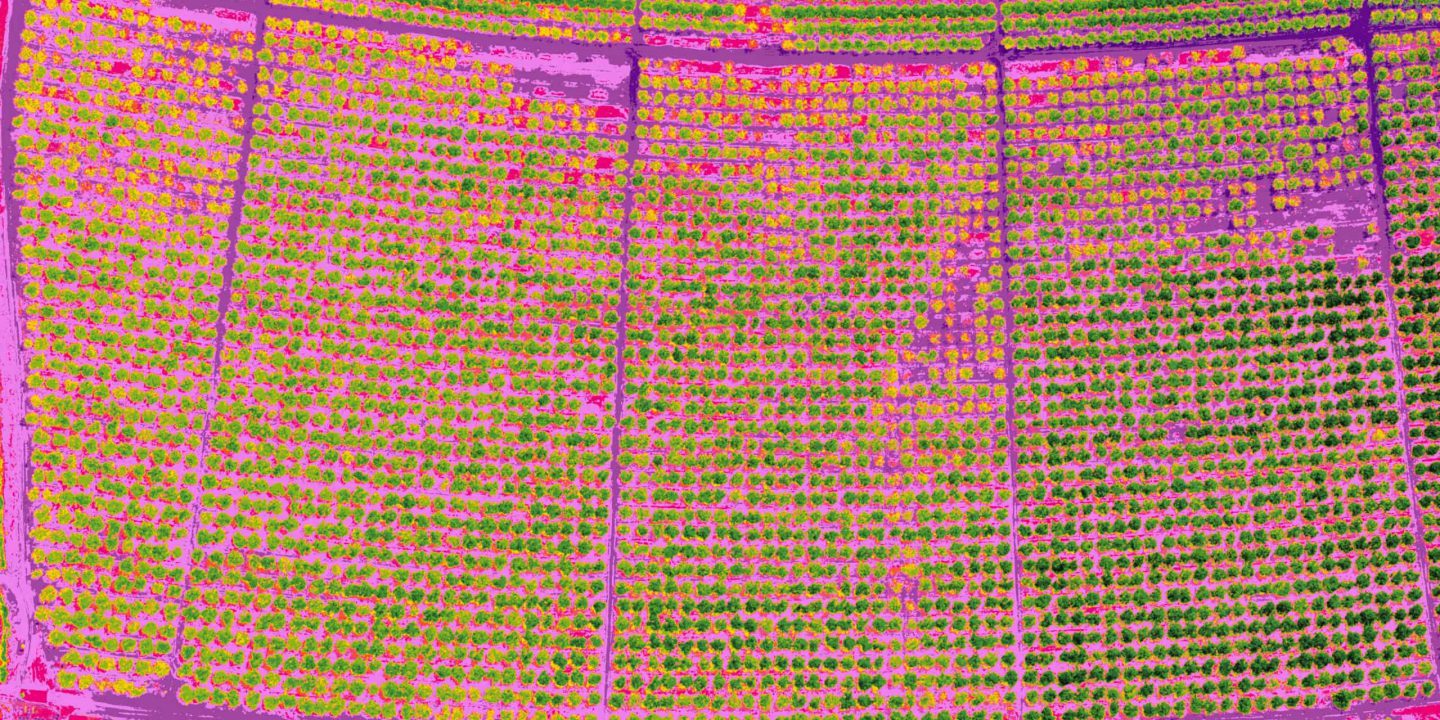

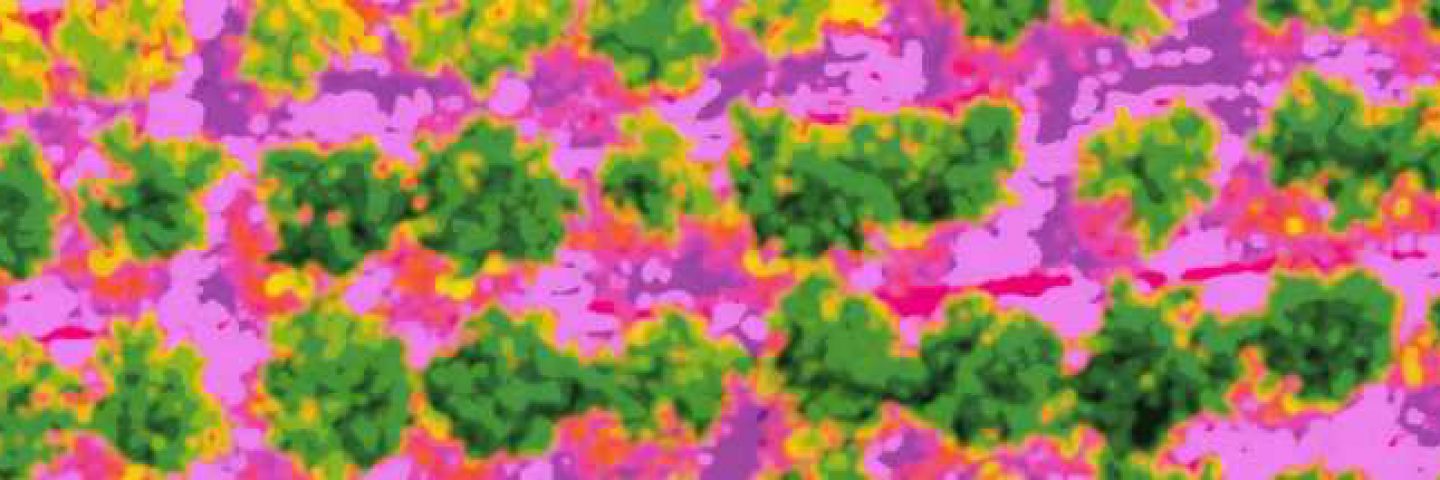

Almonds orchard; Downsampled NDVI orthophoto (100m altitude)

Detail, downsampled by 4!

AI-Enabled Potato-Blight Detection

Low altitude high-resolution multispectral imagery enables the use of Machine-Vision and Machine-Learning (AI) techniques, separating the brown Blight from the green leaves and the earth-brown. Resolution of sub 0.5mm per pixel, resulting from imagery acquisition from 3m altitude above the crop, enables detection of distinctive multispectral signatures of pests, diseases and nutrient deficiencies.

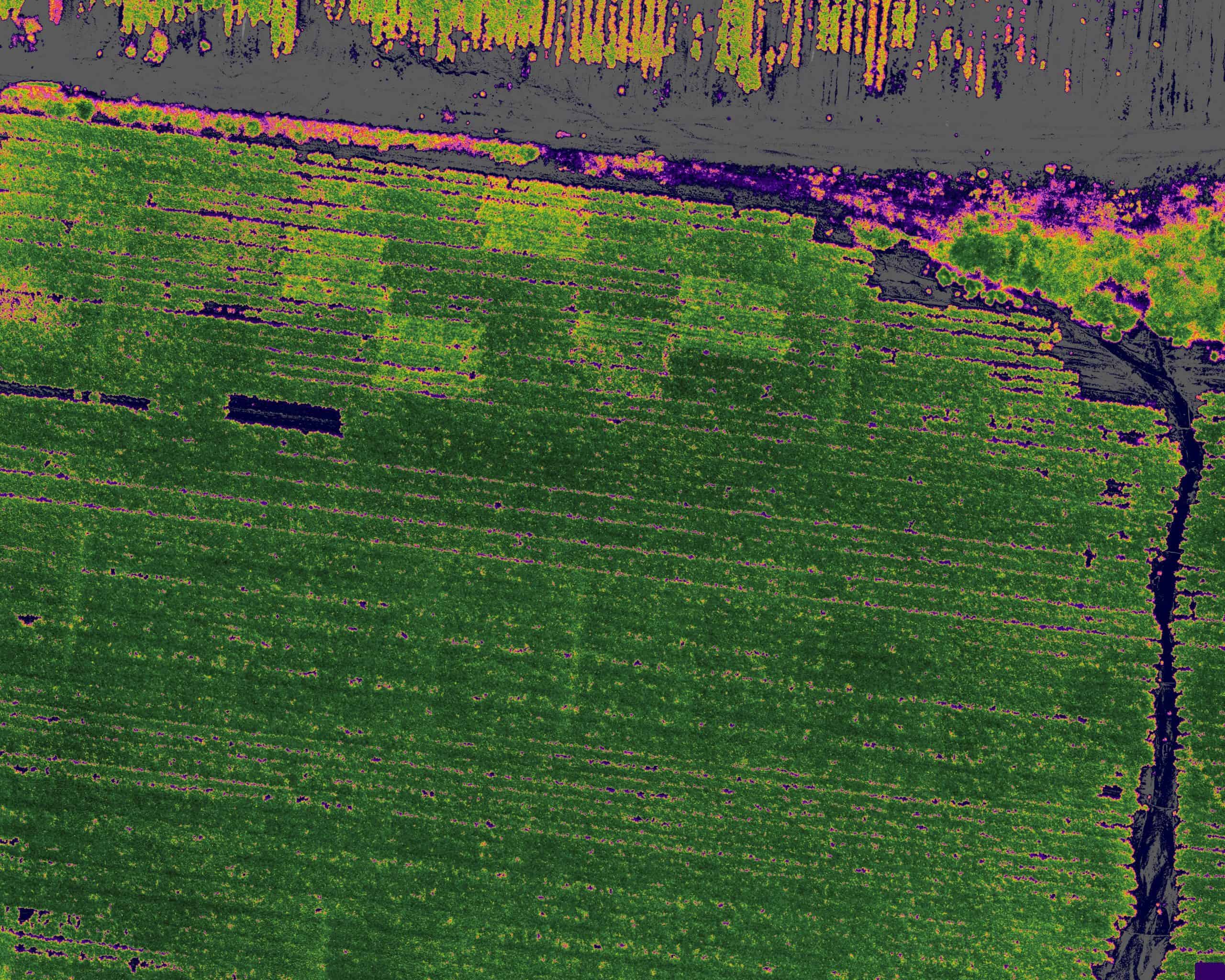

High Altitude NDVI

Agrowing's narrow bands,high-resolution, high dynamic-range sensors, produce the most detailed NDVI maps one can expect. Such detailed NDVI (and similar metrics) maps, are essential for spotting stressed and outlying areas of the field, at an early stage.

Spotting various degrees of blight is demonstrated in this potatoes test-field. The imagery was acquired from 100m altitude using Agrowing's R10C based sensor with NDVI lens.

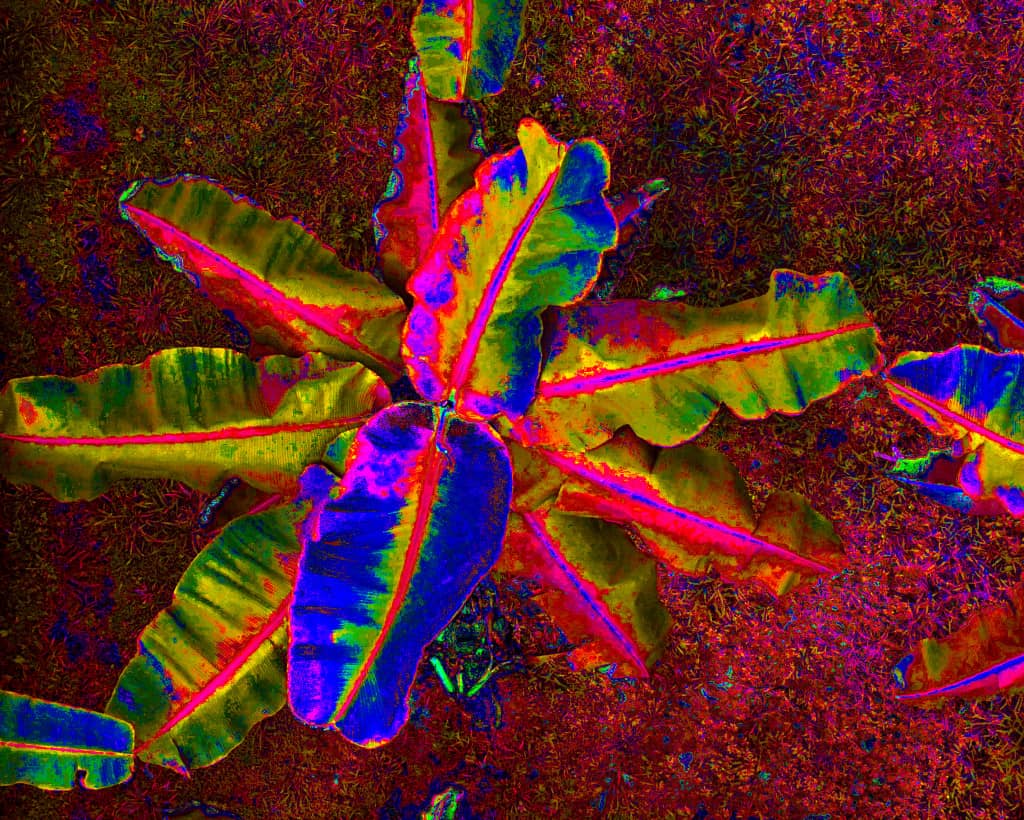

The Invisible Revealed

The progression of Black Sigatoka in Banana leaves, and HLB in Citrus, is invisible at early dates.

Analyzing high-resolution multi-band multispectral data of wide dynamic-range, enables machine-detection of the invisible.